The EPA-proposed Clean Power Plan (CPP), in its current form, could threaten regional electric reliability by forcing generation retirements in regions with declining reserve margins. The CPP proposal was issued on June 2, 2014. It outlines the first emission guidelines for existing fossil-fuel-based power plants, with a goal to reduce power sector emissions by 30 percent by 2030 relative to 2005 levels. It provides state-specific, rate- or mass-based targets to reduce power plant carbon dioxide emissions and guidelines to develop, submit, and implement state plans to meet the targets. The CPP outlines four “building blocks” to achieve the proposed emissions reduction goals including power plant efficiency (heat rate) improvements, fuel-switching (primarily coal to natural gas), increased renewable and nuclear generation and reduced energy demand growth through energy efficiency.

On January 7, 2015, the EPA announced a revised schedule to finalize rulemakings for power plant emission standards under its CPP. By midsummer 2015, the EPA aims to finalize the rules and propose a federal program to cover states that do not submit emissions reduction plans.

The Clean Power plan compliance timeline is as follows:

• Summer 2016 – proposed due date for states to submit compliance plans (complete plans or initial plans with one- to two-year extension requests) and final federal plan to meet goals in areas that do not submit plans

• Summer 2017 – proposed due date for compliance plans with oneyear extension

• Summer 2018 – proposed due date for multi-state compliance plans with two-year extension

• Summer 2020 – proposed beginning of the Clean Power Plan compliance period

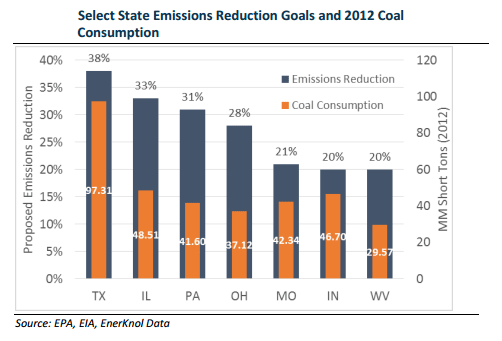

The proposed plan has the potential to significantly impact coal-reliant states with ripple effects across all energy sectors. Texas leads the nation in coal consumption, but its access to natural gas and renewable power will help ease future compliance obligations. Natural gas and renewable energy currently make up approximately 54 and 9 percent of the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) region’s energy mix, respectively. ERCOT natural gas, wind energy, solar energy, energy efficiency and demand response would all likely increase to meet CPP rules.

The proposed plan has the potential to significantly impact coal-reliant states with ripple effects across all energy sectors. Texas leads the nation in coal consumption, but its access to natural gas and renewable power will help ease future compliance obligations. Natural gas and renewable energy currently make up approximately 54 and 9 percent of the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) region’s energy mix, respectively. ERCOT natural gas, wind energy, solar energy, energy efficiency and demand response would all likely increase to meet CPP rules.

The Midcontinent ISO (MISO) covers all, or portions of, 16 states, many of which are coal-reliant states with current low levels of renewable energy capacity. The region relied on coal-fired capacity of more than 70 GW for approximately 70 percent of its annual electricity generation in 2013. MISO estimates the proposed CPP to threaten 14 GW of coal-fired capacity, which, when combined with EPA’s Mercury and Air Toxics Standards, could add up to more than 25 GW of coal-fired capacity retirements. The region will continue its shift toward more natural gas and wind generation sources, which currently combine to provide approximately 20-25 percent of the region’s electricity.

Missouri and West Virginia may find compliance more difficult, as they currently rely on coal-fired capacity for approximately 83 and 93 percent of electricity generation, respectively.

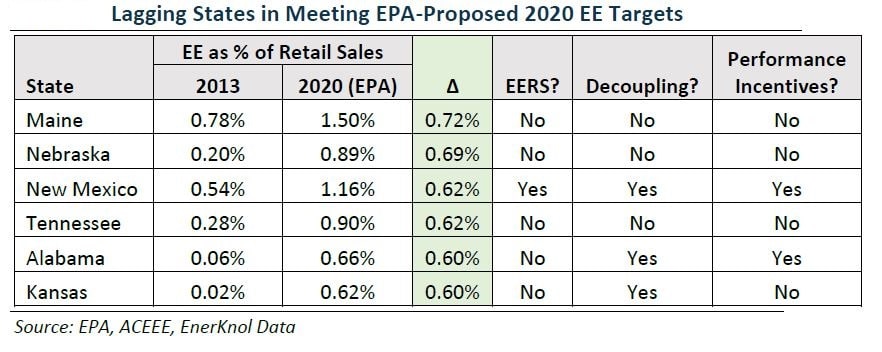

The EPA outlines energy efficiency-driven annual energy use reductions as a percent of the prior year’s electric sales for each state, plateauing at 1.5% by 2025 and continuing thereafter. Several states – Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Hawaii – are already well-above EPA-proposed 2025 energy efficiency targets with the help of energy efficiency resource standards (EERS) and utility revenue decoupling programs. These states may have exhausted many energy efficiency “low hanging fruit” opportunities and would likely turn to other methods of coal-to-gas switching and increased renewable energy to achieve emissions reduction goals.

Energy efficiency opportunities may exist for states lacking notable metrics for it, such as Virginia, Kansas and Louisiana. However, these states may also focus emissions reduction efforts on fuel switching and increased renewable energy, depending on associated infrastructure costs and unique system demand.

EPA’s proposed “Standards of Performance for Greenhouse Gas Emissions from New Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units” would eliminate new coal-fired generation construction without carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology. Broadly, the proposed rule aims to limit emissions from new fossil fuel-fired electric utility generators greater than 25 MW capacity, including utility boilers and natural gas-fired stationary combustion turbines. The draft rule outlines:

EPA’s proposed “Standards of Performance for Greenhouse Gas Emissions from New Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units” would eliminate new coal-fired generation construction without carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology. Broadly, the proposed rule aims to limit emissions from new fossil fuel-fired electric utility generators greater than 25 MW capacity, including utility boilers and natural gas-fired stationary combustion turbines. The draft rule outlines:

• Natural gas-fired stationary combustion turbines – EPA is proposing two limits: 1,000 pounds of carbon dioxide per megawatt-hour (lbCO2/MWh) for units of 85 MW capacity at a 10,000 Btu/kWh heat rate; and 1,100 lbCO2/MWh for smaller units. New natural gas-fired stationary combustion turbines can meet the proposed rule without additional emissions technology add-ons.

• Coal-fired utility boilers – The proposed limits are based on the adoption of carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) technology. The proposed limits are 1,100 lbCO2/MWh over a 12-month operating period; and 1,000-1,050 lbCO2/MWh over an 84-month operating period.

A key question is the extent to which new fossil-fuel utilities will be able to comply if CCS technology is required. Critical to this question is the technology readiness level of CCS, and whether the technology represents the best system of emission reduction (BSER) as required by the Clean Air Act. The BSER must meet demonstrated cost, energy and environmental criteria.

A key question is the extent to which new fossil-fuel utilities will be able to comply if CCS technology is required. Critical to this question is the technology readiness level of CCS, and whether the technology represents the best system of emission reduction (BSER) as required by the Clean Air Act. The BSER must meet demonstrated cost, energy and environmental criteria.

Republican lawmakers, including Rep. Shimkus (R-IL) and Rep. Barton (R-TX) have noted that the CCS technology has not yet been proven at a commercial scale and that the requirement will essentially prevent additional coal plants from coming online. When asked specifically, Energy Secretary Moniz said that the CCS technology for combustion or gasification is at the demonstration level, but that for sequestration, at least one plant is storing 20 million tons, or 60 megatons/year. However, the EPA notes in its draft rule that, “current and planned implementation of CCS projects, combined with the widespread availability and capacity of geological storage sites, makes it clear that the technology is feasible.”

Since 2011, the EPA Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS) has been the most pressing regulation for approximately 1,400 generation units of 25 MW or greater, 1,100 (approximately 310 GW) of which are coal-fired (Figure 10). EPA initially estimated 4.7 GW of coal-fired capacity to retire by 2015 due to this rule. Due to additional financial challenges from low natural gas prices, the EPA estimate has proven to be low. More than 20 GW of coal-fired capacity have retired since 2011. The Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) 2014 Annual Energy Outlook projects nearly 60 gigawatts (GW) of coal retirement by 2020, with 90 percent of retirements taking place before 2016. NERC estimates approximately 40 GW of coal-fired capacity to retire by 2020.

EPA finalized its MATS rule in December 2011 to limit emissions of mercury and other heavy metals from fossil fuel-fired power plants, which are the largest emitters of toxic metals in the U.S. The standard became effective April 16, 2012, with a multi-year phase-in design.

MATS implementation was designed to minimize challenges to the U.S. electricity supply. Compliance begins in April of this year. However, as of October 2014, 133 units have been granted compliance extensions. EPA notes that “reliability critical units” will be given a fifth year, until April 2017, to meet new standards or be retired. Beyond 2017, compliance will be addressed on a case-by-case basis to safeguard grid reliability.

Industry participants, utilities, systems operators and politicians have been vocal about the potential for these rules to disrupt electricity supply. In particular, there are concerns surrounding the possibility that coal-fired power plants may be retired prematurely in light of carrying out potentially expensive retrofits to comply with EPA regulations. Coal-fired generation accounted for approximately 39 percent of the U.S. electricity supply in 2013 and is heavily relied upon in many regions of the U.S., especially the Midwest. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), electricity prices could rise from one percent in California, to about six percent in the region covering Kansas, Oklahoma, and parts of New Mexico, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas and Missouri.